RC Pylon Racing At Sanderson Field

Excitement From The Flight Line

The Sanderson Field RC Flyers (SFRCF) hosts several sanctioned Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) pylon competitions each year. The competitions are sponsored and organized by the Pylon Racers of Puget Sound (PROPS). The events are held at Sanderson Field in Shelton, Washington, the SFRCF home field. Several members of SFRCF are dedicated RC pylon racers and are also members of PROPS.

The Pilots

Tom Strom Sr., Tom Strom Jr., Tom Graves, Edward Graves, Eric Ide, and Dan Nalley are regular participants at the Sanderson Field competitions and are all SFRCF members. They are also members of PROPS and some often serve as contest director (CD) or equipment coordinator.

Tom Strom Sr. and Jr. regularly serve as "caller" for each other during the competitions. Tom Sr. is a long time pylon racer and set the national Q-40 speed record of 57.83 sec on 8/5/2007—and did it at Sanderson Field. His "caller" at that time was Tom Jr. He flew a Nelson LS powered Polecat for the record. Tom Sr. continues to be an inspiration and mentor for pylon racers of all experience levels and also continues to be a fierce competitor. As pilots, both Sr. and Jr. are often among the winners at the end of the competitions.

Tom and Edward Graves fulfilled a pylon racer's dream by competing in their first NATS competition for the 428 Q-500 event in July. Prepping and testing their planes and then packing and shipping them was done just before flying to the competition. Insuring that their equipment arrived safely was quite a challenge. Although they didn't bring home a trophy, they both felt like winners after the great experience of participating in the competition. Tom and "Eddie" are a father and son team and each serves as the "caller" for the other during competitions.

Eric Ide and Dan Nalley are also serious competitors at the Sanderson Field events and are often among the winners for the events they enter. As do many pilots, Eric also served as a caller at a recent event.

The Planes

Specifications for planes flown at AMA sanctioned pylon events are detailed in the AMA competition regulations. The regulations discuss everything from the spinner to the tail. Design specifications in the regulations for each class of competition include those for the wing, fuselage, power plant, landing gear, propeller, construction materials, and many other parts of the plane.

There are three AMA classes (Events) that are flown at Sanderson Field:

- Event 422: Quarter 40 (Q-40),

- Event 424: Sport Quickie, and

- Event 428: Quickie 500 (Q-500).

The Sport Quickie (424) is the entry level event and the planes are the slowest of the three, reaching about 110 mph around the course. Their specification insures that the cost for the plane and engine will be low. The planes are readily available commercially. Wings and tails must be constructed of either all wood or wood sheeting over a solid foam core. An example of a commercially available Sport Quickie is the Great Planes Viper 500.

The Quickie 500 (428) is the next step to high performance RC pylon racing. The "500" refers to the minimum wing area for the class of 500 square inches. Unlike the Sport Quickie, wings and tails manufactured in molds designed to produce hollow core structures can be used. With the engines permitted for this class, the planes can reach speeds around 170mph.

The Quarter 40 (422) is the fastest of the classes. These are the planes that reach the 180-200mph top speeds. Q-40 planes are often all composite and "painted in the mold" resulting in beautiful, sleek—and fast—racers. As specified in the regulations, the planes in this class must also resemble real airplanes:

The Race Course

The race course is defined by three pylons that define a triangular course. Ten laps around the course equals 2.5 miles. The actual distance flown is longer, as Tom Strom Sr. points out:

Pilots fly their aircraft around the course pylons in a counterclockwise direction. The course length is selected to result in 10-lap times between one minute (fast pace) and two minutes (slow pace for beginners). For the quickest aircraft, the speed around the course is typically between 180-200mph.

The Preparation

Preparing for a pylon race actually begins before arriving at the field. For Example, Tom and Edward Graves spent many hours testing their Q-500 aircraft at Sanderson Field before flying off to the NATS—and this does not count the hours of building time. Although Tom and Edward purchase pre-built wings for their Q-500 aircraft, they use their own design for the fuselage. Like other pylon pilots, Tom and Edward pay close attention to every detail of the aircraft in order to increase reliability, reduce drag, and increase performance—before the race begins.

The day before a scheduled competition at Sanderson Field, the PROPS organizers are on site setting up the course. At this time, the field is open for practice flights. Sometimes, before the races actually start in the morning, time is also scheduled for practice flights.

Pilots prepare their aircraft with meticulous attention to detail. The difference between first place and last place is often so close that every aspect of the aircraft's readiness is important. As an example, glow plug elements are frequently checked for color, an indication of the right carburetor adjustment. It is very disappointing to be on the flight line, with the clock counting, and not be able to establish flight control or start an engine before the start-flag drops—and this does happen!

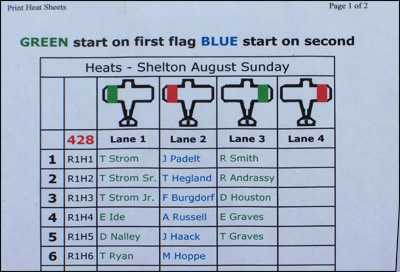

Before the ride to the flight line, pilots check the "heat matrix" for their races, fuel their aircraft, and apply identifying decals to their aircraft that correspond to the starting lanes on the flight line. Note that the heat matrix shows which drop of the flag launches which lanes. The aircraft launches are staggered slightly to prevent congestion at the starting line on takeoff.

After putting on hard hats, pilots board the trailer for the ride to the flight line.

The Flight Line

As new pilots and their callers arrive and ready themselves for a new heat, others begin the ride back to the campsite. For safety purposes, everyone who is not on the flight line must be a minimum of 300 feet from the race course, as defined by the three pylons. At Sanderson Field, the campground, and fueling station are at a much greater distance and the participants are shuttled to and from the flight line.

Among the many responsibilities of the starter is to have pilots perform a control check to insure that the RC system is functioning properly: the transmitter and receiver for each aircraft must be functioning correctly.

When the pilots/callers are ready, the starter starts the 60-second clock. After the clock starts, and because pilots do not want to start their engines too soon, they watch the clock closely until, in their experience, it's the right time to do so.

Pilots have 60 seconds to start their engines and signal their readiness to control the aircraft to the starter. After the engine has been started, the pilot typically moves away from the start line (towards pylon 2 and 3) and prepares to control the aircraft.

After the starter "drops the flag," the caller launches the aircraft and races to the side of the pilot. With the first drop of the flag in a three pilot heat, the two outside lanes launch; the middle lane launches with the second flag.

While the pilot controls the aircraft, the caller "calls" to the pilot when it's time to make a turn. Course judges watch the race carefully to make sure the planes round the pylons on the outside and do not turn a corner by cutting inside the pylon. A "cut" results in an extra lap; two "cuts" and the pilot is out of the race. Other course workers keep track of each lap completed by every aircraft and their time around the course.

As each aircraft completes the last lap, the starter drops his flag to indicate this to the pilot.

When all of the planes have completed their last lap, the starter records the heat results. As specified in the regulations, the pilots will later receive points for the heat as follows:

"After each heat, points shall be awarded based on the order of finish. If the matrix is set up for four-plane heats, the result is four (4) points for first place, three (3) points for second place, two (2) points for third place, and one (1) point for last place. If the matrix is set up for three-plane heats, the winner receives three (3) points, second place two (2), and last place one (1) point. If the matrix is set up for two-plane heats, the winner receives two (2) points and the loser receives one (1). Zero points are awarded for a no-start (DNS), failure to complete the heat (DNF), double cut (XX), or black flag (DQ)."

When the pilots arrive back at pit area, the heat winner must weigh his/her aircraft to insure that it is at or above the minimum allowable weight, as specified in the regulations.

After the last heat of the last day, it's time for the awards ceremony. It's also time for the course-workers prize drawing.

It takes the dedicated effort of many course workers, organizers, and other supporters to put on a pylon event. Although they are not listed in this article, they should all know that their efforts are greatly appreciated. Having volunteers for the course work also frees the pilots and callers to concentrate on preparing and flying the aircraft.

All of the images in the article were taken by the author. The images were taken with an inexpensive, hand-held 5.1MP camera and all received some processing in Adobe Photoshop. Taking images of a Q-40 in flight with such a camera takes a little practice: the camera has to be aimed far ahead of the approaching racer and the shutter clicked to allow the aircraft to fly into the field of view by the time the—slow—shutter actually takes the image.

Special thanks to Patt and Dan Nalley for reviewing the article and offering their comments and suggestions.

Resource Links

Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) –– More information about the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA) regulations for pylon racing.The National Miniature Pylon Racing Association –– The NMPRA is an organization of Pylon Racers whose mission is to promote, organize and standardize the hobby. This website is the home of the NMPRA but our members are spread across the Globe. Take a look around and get involved with the most exciting form of Radio Control.

Notes:

It is now 2020. It has been many years since there has been a pylon race at Sanderson Field. The pylon events were a thrill to watch and were great spectator events—particularly for me, a novice just getting started in RC. In 2008, many of the pilots were national contenders and Tom Strom Sr. was a national record holder. I, for one, am sad that they no longer take place at our field. Most of the photographs were taken with a camera that was really not up to the task. It would have been a pleasure to photograph the events with my more modern SLR camera.